Abstract

AIM: People with chronic conditions must self-manage their health conditions to promote, maintain and restore their health. The Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) provides outcomes for people with chronic conditions to evaluate their knowledge and self-management behaviors. The purpose of this study was to validate the knowledge and self-management Nursing Outcomes Classification focused on hypertension and lipid disorder originally published in the fifth edition of Nursing Outcomes Classification.

METHOD: The Delphi technique was used for this exploratory study. Nurse experts were invited from two areas: standardized nursing terminology and self-management. Definition adequacy, clinical usefulness of measurement scales, and content similarity between indicators of knowledge and self-management outcomes were measured using a structured questionnaire. Descriptive statistics were used to identify modes, means and standard deviations (SD) of the demographic characteristics and the three research variables. The outcome content validity method was used to evaluate each outcome and the associated indicators.

RESULTS: A total of 30 nurse experts participated in this study. The four Nursing Outcomes Classification definitions, two measurement scales, and 110 indicators were validated. The validity was acceptable. However, there were a few indicators that were viewed differently by each expert panel. Further research is recommended.

CONCLUSION: The validated Nursing Outcomes Classification for hypertension and lipid disorder will provide nurses with the clinical importance of indicators. This supports nurses when making clinical decisions, thereby having the ability to evaluate patient outcomes accurately and efficiently.

Introduction

Globally, having multiple chronic conditions is a serious health issue. Hypertension and lipid disorder (LD) specifically have a high prevalence and mortality. More than 20% of adults in the world have been diagnosed with hypertension, and complications from hypertension account for 9.4 million deaths worldwide every year (World Health Organization (WHO), 2015). In 2017, hypertension guidelines were revised by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) (Whelton et al., 2018). These new guidelines will result in nearly half of the United States adult population (46%) being diagnosed as having hypertension and, consequently, these adults will need medical treatment (American College of Cardiology, 2017). Globally, 38.9% of adults had a diagnosis of LD in 2008 (WHO, 2016), and this condition with hypertension leads to significant cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and stroke, leading causes of death worldwide (Grundy et al., 2018).

The prevalence of this dyad of clinical conditions has continuously increased since 2007 and included 55.3% of all Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries in 2015. This is the most prevalent dyad of chronic conditions in the U.S. (Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), 2017). Experts in hypertension and LD strongly recommend that people with these medical diagnoses follow non-pharmacological therapies in daily living (Grundy et al., 2018; Whelton et al., 2018). The strategies include learning about the specific disease process, following complex treatment regimens, monitoring their conditions, modifying lifestyles, and making decisions for handling their health problems as they self-manage their conditions (Grady & Gough, 2014).

Self-management is recognized as a promising strategy for controlling chronic conditions, as patients and their families actively identify challenges and solve problems associated with their illnesses (Grey, Knafl & McCorkle, 2006; Grey, Schulman-Green, Knafl, & Reynolds, 2015; Ryan & Sawin, 2009; Vassilaki et al., 2015). Self-management is affected by numerous factors such as health conditions, physical and social environments, personal perceptions, and health beliefs; however, knowledge is one of the most important factors (Bandura, 1989; da Silva Barreto, Reiners & Marcon, 2014; Pearson, Mattke, Shaw, Ridgely, & Wiseman, 2007). Therefore, patients’ knowledge and health behaviors related to hypertension or LD should be measured to modify their self-management behaviors and improve patient outcomes.

With the expansion and adoption of electronic health records (EHR) due to health care system reform, nursing computerized information systems (CIS) have also developed. The use of standardized nursing terminologies (SNTs) such as nursing diagnoses by NANDA International (NANDA-I), patients’ outcomes from the Nursing Outcomes Classification, and nursing interventions from the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) is required for the effective utilization of CIS (Maas, Scherb, & Head, 2012). When applying SNTs to CIS, nurses can communicate clearly and share information effectively across multiple settings by using the same definitions and labels from the terminologies. It has been documented that the use of SNTs for nursing care plans has contributed to reducing medical errors, supporting decision-making, increasing patient and staff safety, and promoting efficiency and productivity (Butcher & Johnson, 2012; Rutherford, 2008). Moreover, nursing data can be electronically retrieved and evaluated to develop evidence-based nursing knowledge and improve the quality of care. In addition, nurses can deliver health care services in a timely manner and cover nursing workforce shortages through the efficient use of CIS with SNTs that support nursing practice (Butcher & Johnson, 2012; Rutherford, 2008).

Nursing Outcomes Classification is one of the recognized SNTs by the American Nursing Association and is a classification system of nursing-sensitive patient outcomes that assists nurses and other health care providers to evaluate and quantify the status of the patient, caregiver, family or community (Moorhead, Swanson, Johnson & Maas, 2018). Nurses play a key role in implementing nursing care plans, using these terminologies to assist patients to self-manage and reduce the risks associated with these conditions. Nursing Outcomes Classification outcomes include Knowledge: Hypertension Management, which was published in the 4th edition in 2008 and revised in 2013 to measure the level of knowledge of people diagnosed with hypertension. The Knowledge: Lipid Disorder Management, Self-Management: Hypertension, and Self-Management: Lipid Disorder outcomes were introduced in the 5th edition (2013) to measure the level of knowledge of people diagnosed with LD and self-management behaviors (Moorhead et al., 2013).

Although some outcomes were validated in previous research (Moorhead, Johnson, & Maas, 2004), the four Nursing Outcomes Classifications focused on knowledge and self-management of hypertension and LD have not been validated. Also, they are published in the latest edition of Nursing Outcomes Classification without any revisions (Moorhead et al., 2018). Since the outcomes are used as measurement tools, validation of the four outcomes with their definitions, indicators and measurement scales is required before they are widely used across health settings to provide reliable evidence (Gray, Grove, & Sutherland, 2017; Johnson et al., 2012). The purpose of this study was to validate the knowledge and self-management Nursing Outcomes Classification outcomes for hypertension and LD. This validation included their definitions, indicators, measurement scales, and content.

Literature on Nursing Outcomes Classification Validation

One of the main purposes of Nursing Outcomes Classification is to evaluate patient, family and community health outcomes as a measurement tool. According to Polit, instruments should have and report acceptable validity and reliability. The meaning of validity is the degree to which an instrument is measuring what it is supposed to be measuring (Polit, 2010, p.217). Validation of NOC outcomes is required to provide empirical evidence, so nurses can be confident in making clinical judgments for evaluation of patient outcomes with NOC outcomes.

At the beginning of Nursing Outcomes Classification development, several studies of the outcomes were validated to provide clinical evidence of the validity, reliability, sensitivity and usefulness of the outcomes and measurement scales (Head et al., 2004; Head et al., 2003; Keenan, Stocker, Barkauskas, Johnson, et al., 2003; Maas et al., 2002; Moorhead, Johnson, Maas, & Reed, 2003; Scherb, Johnson, & Maas, 1998). These studies reported that NOC outcomes had acceptable psychometric properties as a measurement tool. After publishing the 3rd edition in 2004, many studies focused on the effects of using NOC outcomes and the most frequent NOC outcomes for specific populations (Head, Scherb, Maas, et al., 2011; Head, Scherb, Reed, et al., 2011; Lunney, Parker, Fiore, Cavendish, & Pulcini, 2004; Muller-Staub et al., 2007; Scherb et al., 2011). These studies developed nursing knowledge through validation. Recent validation studies have emphasized the linkage among NANDA-I diagnoses, NIC interventions, and NOC outcomes. Some studies validated the most important NOC outcomes for specific NANDA-I diagnoses focused on specific populations or conditions (da Silva et al., 2011; de Fátima Lucena, Holsbach, Pruinelli, Serdotte Freitas Cardoso, & Schroeder Mello, 2013; Morilla-Herrera et al., 2011; Seganfredo & Almeida Mde, 2011). These studies provided not only acceptable psychometric properties of NOC outcomes but also the importance and effects of using SNTs in clinical settings. In the latest edition (6th), 52 new outcomes were developed and added. As a new measurement tool, these new outcomes should be validated to provide clinical evidence and nursing knowledge to nurses.

Methods

A descriptive exploratory design was used to validate the knowledge and self-management Nursing Outcomes Classification outcomes focused on hypertension and LD using an electronic survey. A Delphi technique was used to validate the outcomes with their definitions, indicators and measurement scales. Electronic surveys using the Delphi technique were sent twice to obtain a clear consensus among a sample of nurse experts (Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004). Approval from the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board was granted for the study on September 2, 2014. The participants completed surveys from February 12 to July 1, 2015.

Sample

Self-management and Nursing Outcomes Classification were important concepts of this study. Two panel categories were required to validate the NOC outcomes according to these concepts: 1) nurse experts in SNT such as NANDA-I diagnoses, NOC and NIC, and 2) nurse experts in self-management. Based on Fehring’s suggestions for conducting validation studies (Fehring, 1987, 1994), at least a master’s degree in nursing was required for nurse participants. Detailed inclusion criteria are as follows:

Panel for SNT (P-SNT): nurses who were members of the NANDA-I or fellows of the Center for Nursing Classification & Clinical Effectiveness (CNC), and had at least a master’s degree in nursing were invited.

Panel for self-management (P-SM): nurses who were members of two research interest sections (RIS) Health Promoting Behaviors Across Lifespan and Self Care in the Midwest Nursing Research Society and had at least a master’s degree in nursing were invited. According to associations among self-management, chronic disease, health behavior change, and health promotion, members in the two RISs were invited as nurse experts in self-management.

Questionnaires and variables

Two electronic questionnaires were developed to validate the four Nursing Outcomes Classification outcomes, Knowledge: Hypertension Management; Self-Management: Hypertension; Knowledge: Lipid Disorder Management; and Self-Management: Lipid Disorder. Each survey set included the knowledge and self-management outcomes of hypertension and LD respectively. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: introduction of the survey, the variables about the two NOC outcomes, and general information. The developed questionnaires were evaluated by two doctoral students in nursing before sending to the participants. Definition adequacy, content validity, clinical usefulness, and content similarity were the variables in this study. Definition adequacy was measured to capture the essence of the outcome definition adequately. A 5-point scale was used as 1-not at all adequate; 2-slightly; 3-moderately; 4-quite; and 5-perfectly adequate to describe each outcome. Clinical usefulness was measured to determine the degree of relevance of use of the measurement scale for measuring the outcome clinically. A 5-point scale was used as 1-never relevant; 2-slightly; 3-moderately; 4-quite; and 5-very relevant to measure each indicator. Content validity of each outcome and the indicators was measured to evaluate the degree of content importance. A 5-point scale was used as 1-not at all important; 2-slightly; 3-moderately; 4-quite; and 5-very important. Content similarity was measured to confirm a degree of similarity between the indicators of knowledge and self-management outcomes. A 5-point scale was used as 1-not matched; 2-slightly; 3-partially; 4-mostly; and 5-perfectly matched.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to identify modes, means and standard deviations of the demographic characteristics and research variables. Higher means indicated that the definition adequately described the essence of the outcome; the measurement scale can be used to measure indicators in clinical settings; and the indicators in the two outcomes are interrelated to evaluate patient knowledge and behaviors. Mann Whitney U-tests were used to compare the means of variables between the two panel groups with the significance level as 0.05.

Johnson and Maas (1998) developed the outcome content validity (OCV) method based on Fehring’s technique (Fehring, 1987, 1994) to identify importance ratios for each indicator and to calculate outcome content validity scores of NOC outcomes. Fehring’s (1987) work was originally developed to validate nursing diagnoses. This method classified the importance ratios for the defining characteristics of nursing diagnoses into major and minor. These categories were adopted for use in the validation of NOC outcomes in early research (Johnson & Maas, 1998). Further validation studies were conducted using three categories for the importance of indicators based on calculated ratios: critical (ratios ≥ 0.80), supplemental (0.799 > ratios ≥ 0.60), and unnecessary (0.60 > ratios) (de Fátima Lucena, 2013; Head, Maas & Johnson, 2003; Head et al., 2004; Oh & Moorhead, 2019; Scherb, Rapp, Johnson & Maas, 1998; Seganfredo & Almeida, 2011). Detailed calculation and interpretation approaches are as follows (Johnson & Maas, 1998):

- Experts’ ratings of 1 to 5 were weighted as follows: 5=1.0; 4=0.75; 3=0.50; 2=0.25; and 1=0.

- Weighted scores for each indicator were summed and divided by the total number of the responses to produce indicator ratios (the highest ratio is 1.0).

- Based on the ratios, indicators were categorized in the three categories of importance: critical, supplemental and unnecessary.

- Weighted scores for each indicator in the critical and supplemental categories were summed and divided by the number of the indicators to calculate the outcome content validity scores of the outcomes.

The indicators in the unnecessary category were not included to calculate o utcome content validityscores. An outcome content validity score of a NOC outcome was identified using the mean of ratios of indicators categorized in the critical and supplemental categories. The data were analyzed using SPSS WIN 21.0 and Microsoft Excel 2010.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The outcomes related to Hypertension

Thirteen of 61 invited experts (21.3%) from both panels responded (Table 1). Five of 16 nurse experts (31.2%) in P-SNT and eight of 45 nurse experts (18%) in P-SM participated in the first round. In the second round, only respondents in the first round were invited, and four of five respondents (80%) in P-SNT and four of eight respondents (50%) in P-SM completed the survey. The average number of years of experience in nursing was 30.15 years (SD=12.85). The number of years of specialty experience ranged from two to 37 years, with an average of 15 years (SD=11.77). Many of the respondents (84.6%) currently worked in nursing and most (77%) worked at a college or university as a researcher or educator. Among 16 participants, three nurse experts specifically worked with patients with hypertension or cardiovascular diseases. All the experts had experience in using SNTs.

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of the Group for the Outcomes of Hypertension (n=13)

The outcomes related to Lipid Disorder

Seventeen of 63 invited experts (27%) responded to this survey in the first round (Table 2). Seven of 16 (43.7%) and 10 of 47 (21.2%) of nurse experts participated in this survey as the P-SNT and P-SM, respectively. Five of the seven in P-SNT and five of 10 experts in P-SM responded to the second round. The average experience in nursing was 25.03 years. The average experience in specialty was 16.9 years, and the range was from one to 38 years. Most of the participants (80%) were employed in nursing. More than 70% of respondents worked at a college or university, and less than a quarter of them worked at a hospital or ambulatory setting. Ten of 17 (58.8%) had experience in using SNTs (Table 2).

Table 2: Demographic Characteristics of the Group for the Outcomes of Lipid Disorder (n=17)

Validation of the Nursing Outcome Knowledge: Hypertension Management

The definition of this outcome is “Extent of understanding conveyed about high blood pressure, its treatment, and the prevention of complications” (Moorhead et al., 2013, p. 320). Most of the raters indicated that the definition was quite adequate (mode=4, Table 3). The average score of definition adequacy by all of respondents was 4.23 out of 5 (SD=0.73). The means by the two panels were statistically different (p=0.017). Most experts in P-SNT evaluated the definition as perfectly adequate, whereas some experts in P-SM identified the definition was moderately or quite adequate. The indicators are measured using a 5-point scale as 1-no knowledge; 2-limited knowledge; 3-moderate knowledge; 4-substantial knowledge; and 5-extensive knowledge with a not applicable (NA) option (Moorhead et al., 2013, p. 320). The mean of clinical usefulness rated by all respondents was 4.0 out of 5 (SD=0.11). However, most raters evaluated that the scale was very relevant (mode=5). The means by the two panels were not statistically different, but the mean by P-SNT was a little higher (Table 3).

Table 3: Means and Modes of Definition Adequacy, Clinical Usefulness, and Content Similarity of the Outcomes (n=13)

A total of 31 indicators were rated by the respondents to build the outcome content validity, and the total outcome content validity score of the outcome was 0.864 out of 1.0 (Table 4). Based on the total indicator ratio (IR), 29 indicators were evaluated as critical, and two indicators were designated as supplemental: Strategies to manage stress, and Available support groups. The highest-rated indicator was Normal range for diastolic blood pressure with 0.94 out of 1.0 IR. Through the two rounds, there were six indicators categorized differently by the panels. P-SM considered that five of six indicators were not critical but supplemental for this outcome.

Table 4: The Most Important and Debatable Indicators of Knowledge: Hypertension Management Based on Indicator Ratio (n=13)

Validation of the Nursing Outcome Self-Management: Hypertension

The definition of this outcome is “Personal actions to manage high blood pressure, its treatment, and to prevent complications” (Moorhead et al., 2013, p. 491). Most raters determined that the definition was quite adequate (mode=4, Table 3). The means by the two panels ranged from 3.63 (SD=0.74) to 4.60 (SD=0.55). The mean of P-SNT was statistically higher (p=0.029) than P-SM. The indicators of this outcome are measured using a 5-point scale as 1-never demonstrated; 2-rarely demonstrated; 3-sometimes demonstrated; 4-often demonstrated; and 5-consistently demonstrated with an NA option (Moorhead et al., 2013, p. 491). The clinical usefulness of this scale was identified as very relevant (mode=5) to evaluate indicators. The mean of clinical usefulness rated by all of respondents was 4.15 (SD=0.90). Indicators between two outcomes Knowledge: Hypertension Management and Self-Management: Hypertension were rated as mostly matched (mode=4) by most respondents. The means of content similarity by the two panels were 4.20 (SD=0.88) and 4.0 (SD=0.53), and the average mean was 4.08 out of 5 (SD=0.64).

Respondents evaluated a total of 33 indicators in this outcome. Twenty-one of 33 indicators were identified as critical and twelve indicators were determined as supplemental. The total outcome content validity score of this outcome was 0.826. The indicator Uses medication as prescribed with 0.96 IR was the highest-rated. This outcome has the most indicators and more than one-third were evaluated as supplemental (Table 5). Eight indicators were categorized differently by the panels, and five indicators were considered as supplemental by both panels. One indicator Uses support group was evaluated as unnecessary by P-SNT with 0.50 IR.

Table 5: The Most Important and Debatable Indicators of Knowledge: Hypertension Management Based on Indicator Ratio (n=13)

Validation of the Nursing Outcome Knowledge: Lipid Disorder Management

The definition of this outcome is “Extent of understanding conveyed about hyperlipidemia, its treatment, and the prevention of complications” (Moorhead et al., 2013, p. 327). Most of the raters indicated that the definition was quite adequate (mode=4, Table 6). The average score by all of respondents was 3.88 (SD=0.86). The mean by P-SNT was a little higher but there was no significant difference (p=0.310). The indicators are measured using a 5-point scale as 1-no knowledge; 2-limited knowledge; 3-moderate knowledge; 4-substantial knowledge; and 5-extensive knowledge with an NA option (Moorhead et al., 2013, p. 327). The mean of clinical usefulness evaluated was 4.29 (SD=0.85). Most raters determined that this measurement scale was very relevant (mode=5) to evaluate indicators.

Table 6: Means and Modes of Definition Adequacy, Clinical Usefulness, and Content Similarity of the Outcomes (n=17)

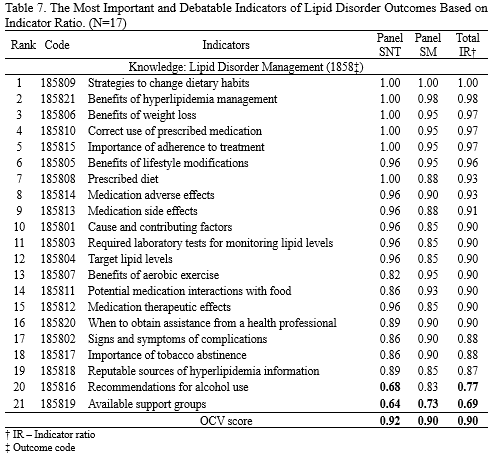

A total of 21 indicators were rated by respondents to build content validity. Nineteen of 21 indicators were evaluated as critical, and two indicators were designated as supplemental. The importance of this outcome calculated by the average ratio of all indicators was identified as critical (OCV=0.904). The highest-rated indicator was Strategies to change dietary habits with a perfect IR. One of the supplemental evaluated indicators Recommendations for alcohol use was categorized differently by the panels (Table 7).

Table 7: The Most Important and Debatable Indicators of Lipid Disorder Outcomes Based on Indicator Ratio (n=17)

Validation of the Nursing Outcome Self-Management: Lipid Disorder

The definition of this outcome is “Personal actions to manage hyperlipidemia, its treatment, and to prevent complications” (Moorhead et al., 2013, p. 494). The mean of definition adequacy identified was 4.29 (SD=0.92). The means by the two panels were similar without a statistical difference: 4.43 (SD=1.13) and 4.20 (SD=0.79, Table 6). The indicators are measured using a 5-point scale as 1-never demonstrated; 2-rarely demonstrated; 3-sometimes demonstrated; 4-often demonstrated; and 5-consistently demonstrated with an NA option (Moorhead et al., 2013, p. 494). The clinical usefulness of this measurement scale was identified as quite relevant (mode=4). The mean of clinical usefulness evaluated by all respondents was 4.06 (SD=1.14). The content of indicators in the pair Knowledge: Lipid Disorder Management and Self-Management: Lipid Disorder was mostly matched (mode=4). The mean of the content similarity by all respondents was 4.35 (SD=0.61, Table 6).

Respondents evaluated a total of 25 indicators of this outcome. Twenty-four of 25 indicators were identified as critical, and one indicator was evaluated as supplemental: the indicator Avoids second hand smoke with 0.75 IR. The average ratio of all indicators for the importance was determined to be critical (OCV=0.888). The importance of six indicators was categorized differently by the two panels (Table 8). These six indicators are the same indicators rated as not at all important for this outcome in the second round by P-SNT.

Table 8: The Most Important and Debatable Indicators of Lipid Disorder Outcomes Based on Indicator Ratio (n=17)

Discussion

This study tested the four knowledge and self-management NOC outcomes with their definitions, measurement scales, and indicators focused on hypertension and LD by nurse experts. All the definitions were evaluated as quite adequate. However, the means by P-SM were lower than the means by P-SNT. Three of four definitions were evaluated as moderately or quite adequate to capture the essence of the outcomes. The experts in P-SM had expertise in self-management and health behavior promotion rather than standardized terminologies. Their clinical perspectives would have affected the results. Previous validation studies about indicators and their operational definitions in Nursing Outcomes Classification reported that nurses used indicators with their operational definitions implemented the Nursing Outcomes Classification more clearly and showed greater concordance among users (Chantal Magalhaes da Silva, de Souza Oliveira-Kumakura, Moorhead, Pace, & Campos de Carvalho, 2017; da Silva et al., 2011). Although the means by all respondents were acceptable, each definition should be reviewed and carefully revised for nurses in clinical settings to select and use them accurately.

About the clinical usefulness, most respondents evaluated the scales as very relevant to measure knowledge and behaviors. There was a Nursing Outcomes Classification validation study that reported clinical usefulness of some NOC outcomes previously (Maas et al., 2002). This early study analyzed users’ comments and feedback about difficulties of the outcomes with their measurement scales and reported acceptable clinical usefulness. This study evaluated clinical usefulness of knowledge and self-management outcomes with quantitative values. The results of this study provided additional evidence of use of NOC outcomes to evaluate patients’ outcomes.

Content validity of each outcome and the indicators were tested using the outcome content validity method and IR. A total of 110 indicators from the four NOC outcomes were evaluated: 85% of them were categorized in the critical level and 15% of them (17/110) were categorized in the supplemental level. There were no “unnecessary” indicators identified in this study. The top five indicators in each outcome to measure knowledge and behaviors for hypertension and LD were exactly matched with the guidelines of hypertension and LD by ACC and AHA (Grundy et al., 2018; Whelton et al., 2018). Although all indicators were evaluated as necessary for outcome evaluation, there were 17 indicators identified as supplemental. Among the 17 indicators, 12 indicators were included in the Self-Management: Hypertension outcome. Further evaluations and revisions of these indicators by nurses who have expertise in hypertension are strongly recommended. Interestingly, indicators related to support groups were the lowest-rated in this study (Tables 4, 5 & 7). Most of the knowledge and self-management outcomes in Nursing Outcomes Classification include indicators focused on support groups. Further revisions of these outcomes should evaluate if this is essential content and important behaviors to assist patients with hypertension or LD to improve their health.

The other finding is that there were 13 indicators rated differently by the expert groups. Even though they were categorized as critical based on the total IR, one panel evaluated them as supplemental. In terms of linguistic accuracy and clinical importance, additional research may be needed with an emphasis on current standards of care for patients with these two clinical conditions.

There are no standard rules of the number of indicators for the development of NOC outcomes. As the outcomes were reviewed during the development phase, nurses tended to add additional indicators to address the needs of different populations of patients, such as difference in age or health status. However, a shorter list of items is usually considered better for measuring a concept to minimize response bias results from boredom or fatigue (Hinkin, Tracey, & Enz, 1997). It is recommended that the Nursing Outcomes Classification team continue to evaluate the importance of the indicators rated by clinical experts using the outcome content validity method and revise the indicators iteratively.

Content similarity was evaluated to examine how connected the knowledge and behavior indicators were in these pairs of outcomes. To perform self-management behaviors accurately, the patient needs correct knowledge and information about their conditions (Grady & Gough, 2014; Pearson et al., 2007) . Thus, knowledge and behavior measurements should be related to each other to evaluate outcomes precisely. The results identified that knowledge and behavior indicators were mostly comparable to each other. Nurses caring for people with hypertension or LD can evaluate their patients’ knowledge and self-management outcomes. However, this is the first study to validate content similarity between knowledge and self-management NOC outcomes focused on hypertension and LD. Validating content similarity between knowledge and self-management behaviors is recommended for further studies to support self-management for other populations.

Limitations and recommendations

There were two limitations for this study. First, the results of this study could not be generalized because the English version was only validated by nurse experts in the U.S. The Nursing Outcomes Classification has been translated into 11 different languages and the Spanish version is also commonly used. To establish concrete evidence, further validation studies with nurse experts from various cultures and counties are recommended. Second, there was lack of content experts with expertise in hypertension and LD in this study. The majority of participants did not specifically work with patients with hypertension or LD. Thus, their perspective and opinions were not matched with the gold standards for hypertension or LD care. For example, the indicator Eliminates tobacco use in both self-management outcomes was identified as supplemental (Tables 5 & 8). However, smoking cessation is one of the most important recommended behavior changes by ACC and AHA. Therefore, soliciting content-specific experts is recommended to build credible content validity. Fehring (1987) identified that obtaining nurse experts in a specific specialty area was one of the difficulties in implementing this type of validation research. Finding experts to review outcomes should be an important part of determining qualifications for expert reviews.

Conclusion

This study was conducted to validate the four NOC outcomes focused on knowledge and self-management for people with hypertension or LD. The results of this study provided evidence on these four NOC outcomes that they have acceptable definition adequacy, clinical usefulness, indicator importance, and content similarity. However, iterative evaluations and revisions of indicators by content-specific experts are needed to develop clinically practical outcomes. The findings of this study will support critical decision-making of nursing students and health care providers. The students can learn which indicators should be evaluated critically for patients with hypertension or LD. Health care providers can obtain accurate patient data, determine the effects of applied health interventions, and communicate clearly by using these validated outcome measurements.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog or by commenters are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HIMSS or its affiliates.

Online Journal of Nursing Informatics

Powered by the HIMSS Foundation and the HIMSS Nursing Informatics Community, the Online Journal of Nursing Informatics is a free, international, peer reviewed publication that is published three times a year and supports all functional areas of nursing informatics.

American College of Cardiology. (2017). New ACC/AHA high blood pressure guidelines lower definition of hypertension. ACC News Story.

Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of childe development, Volume 6. Six theories of child development. (pp. 1-60). JAI Press.

Butcher, H., & Johnson, M. (2012). Use of linkages for clinical reasoning and quality improvement. In M. Johnson, S. Moorhead, G. Bulechek, H. Butcher, M. Maas, & E. Swanson (Eds.), NOC and NIC linkages to NANDA-I and clinical conditions: Supporting critical reasoning and quality care (3 ed., p. 11-23). Mosby Elsevier.

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2017). Co-morbidity. Chronic Conditions.

Chantal Magalhaes da Silva, N., de Souza Oliveira-Kumakura, A. R., Moorhead, S., Pace, A. E., & Campos de Carvalho, E. (2017). Clinical validation of the indicators and definitions of the nursing outcome "Tissue Integrity: Skin and Mucous Membranes" in people with diabetes mellitus. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge, 28(4), 165-170. doi:10.1111/2047-3095.12150

da Silva, V. M., Lopes, M. V. de O., de Araujo, T. L., Beltrão, B. A., Monteiro, F. P. M., Cavalcante, T. F., Moreira, R. P., & Santos, F. A. A. S. (2011). Operational definitions of outcome indicators related to ineffective breathing patterns in children with congenital heart disease. Heart & Lung : The Journal of Critical Care, 40(3), e70–e77. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2010.12.002

da Silva Barreto, Reiners, A. A. & Marcon, S. S. (2014). Knowledge about hypertension and factors associated with the non-adherence to drug therapy. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagen, 22(3), 491-498.

de Fátima Lucena, A., Holsbach, I., Pruinelli, L., Serdotte Freitas Cardoso, A., Schroeder Mello B. (2013) Brazilian validation of the nursing outcomes for acute pain. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge. 24(1), 54–58.

Fehring, R. J. (1987). Methods to validate nursing diagnoses. Heart & Lung : The Journal of Critical Care, 16, 625-629.

Fehring, R. J. (1994). The Fehring model: Symposium on validation models. In R.M. Carroll-Johnson & M. Paquette (Ed.), Classification of nursing diagnoses: Proceedings of the tenth conference North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (p. 55-62). Lipincott.

Grady, P. & Gough, L. (2014). Self-management: A comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. Farming Health Matters. 104(8), e25-e31.

Gray, J., Grove, S. K., & Sutherland, S. (2017). Burns and Grove's The practice of nursing research (8th ed.). Elsevier.

Grey, M., Knafl. K. & McCorkle, R. (2006). A framework for the study of self-and family management of chronic conditions. Nursing Outlook, 54(5), 278-286.

Grey, M., Schulman-Green, D., Knafl, K. & Reynolds, N. R.(2015). A revised self- and family management framework, Nursing Outlook, 63(2), 162-170.

Grundy, S. M., Stone, N. J., Bailey, A. L., Beam, C., Birtcher, K. K., Blumenthal, R. S., Braun, L. T., de Ferranti, S., Faiella-Tommasino, J., Forman, D. E., Goldberg, R., Heidenreich, P. A., Hlatky, M. A., Jones, D. W., Lloyd-Jones, D., Lopez-Pajares, N., Ndumele, C. E., Orringer, C. E., Peralta, C. A., & Saseen, J. J. (2019). 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 139(25), e1082–e1143. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625

Head, B. J., Maas, M. & Johnson, M. (2003). Validity and community-health nursing sensitivity for community health nursing in older clients. Public Health Nursing, 20(5), 385-398.

Head, B. J., Aquilino, M. L. Johnson, M., Reed, D., Maas, M. & Moorhead, S. (2004). Content validity and nursing sensitivity of community-level outcomes from the Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC). Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(3), 251-259.

Head, B. J., Scherb, C. A., Maas, M. L., Swanson, E. A., Moorhead, S., Reed, D., . . . Kozel, M. (2011). Nursing clinical documentation data retrieval for hospitalized older adults with heart failure: Part 2. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications, 22(2), 68-76. doi:10.1111/j.1744-618X.2010.01177.x

Head, B. J., Scherb, C. A., Reed, D., Conley, D. M., Weinberg, B., Kozel, M., . . . Moorhead, S. (2011). Nursing diagnoses, interventions, and patient outcomes for hospitalized older adults with pneumonia. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 4(2), 95-105. doi:10.3928/19404921-20100601-99

Hinkin, T. R., Tracey, J. B., & Enz, C. A. (1997). Scale construction: Developing reliable and valid measurement instruments. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 21(1), 100-120. doi:doi:10.1177/109634809702100108

Johnson, M., & Maas, M. (1998). The nursing outcomes classification. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 12(5), 9-20.

Johnson, M., Moorhead, S., Bulechek, G., Butcher, H., Maas, M., & Swanson, E. (2012). NOC and NIC linkages to NANDA-I and clinical conditions: Supporting critical reasoning and quality care (3 ed.). Mosby Elsevier.

Keenan, G., Stocker, J., Barkauskas, V., Johnson, M., Maas, M., Moorhead, S., & Reed, D. (2003). Assessing the reliability, validity, and sensitivity of nursing outcomes classification in home care settings. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 11(2), 135-155.

Lunney, M., Parker, L., Fiore, L., Cavendish, R., & Pulcini, J. (2004). Feasibility of studying the effects of using NANDA, NIC, and NOC on nurses' power and children's outcomes. CIN: Computers, informatics, nursing: CIN, 22(6), 316-325.

Maas, M. L., Reed, D., Reeder, K. M., Kerr, P., Specht, J., Johnson, M., & Moorhead, S. (2002). Nursing outcomes classification: a preliminary report of field testing. Outcomes Management, 6(3), 112-119.

Maas M, Scherb C, & Head B. (2012). Use of NNN in computerized information systems. In M Johnson, S Moorhead, G Bulechek, H Butcher, M Maas, & E Swanson (Eds.), NOC and NIC linkages to NANDA-I and clinical conditions: Supporting critical reasoning and quality care (3 ed., pp. 24-34). Mosby

Moorhead, S., Johnson, M., & Maas, M. (Eds.). (2004). Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) (3 ed.). Mosby.

Moorhead, S., Johnson, M., Maas, M., & Reed, D. (2003). Testing the nursing outcomes classification in three clinical units in a community hospital. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 11(2), 171-181.

Moorhead, S., Johnson, M., Maas, M. L., & Swanson, E. (2013). Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC): Measurement of health outcomes (5 ed.). Mosby.

Moorhead, S., Swanson, E., Johnson, M., & Maas, M. L. (2018). Nursing Outcomes Classificatin (NOC): Measurement of health outcomes (6 ed.). Elsevier.

Morilla-Herrera, J. C., Morales-Asencio, J. M., Fernandez-Gallego, M. C., Cobos, E. B., & Romero, A. D. (2011). Utility and validity of indicators from the nursing outcomes classification as a support tool for diagnosing Ineffective Self Health Management in patients with chronic conditions in primary health care. Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra, 34(1), 51-61.

Muller-Staub, M., Needham, I., Odenbreit, M., Lavin, M. A., & van Achterberg, T. (2007). Improved quality of nursing documentation: results of a nursing diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes implementation study. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications, 18(1), 5-17. doi:10.1111/j.1744-618X.2007.00043.x

Oh, H. & Moorhead, S. (2019). Validation of the knowledge and self-management nursing outcomes classification for adults with diabetes. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 37(4), 222-228.

Okoli, C., & Pawlowski, S. D. (2004). The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Information & Management, 42(1), 15-29.

Pearson, M. L., Mattke, S., Shaw, R., Ridgely, M. S., & Wiseman, S. H. (2007). Patient self-management support programs: An evaluation (08-0011). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Polit, D. F. (2010). Statistics and data analysis for nursing research (2 ed.). Upper Pearson.

Rutherford, M. (2008). Standardized nursing language: what does it mean for nursing practice? OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 13(1), DOI: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol13No01PPT05

Ryan, P. & Sawin, K. J. (2009). The individual and family self-management theory: Background and perspectives on context, process and outcomes. Nursing Outlook, 57(4), 217-225.

Scherb, C. A., Rapp, C. G., Johnson, M. & Maas, M. (1998). The Nursing outcomes Classification validation by rehabilitation nurses. Rehabilitation Nursing, 32(4), 174-191.

Scherb, C.A., Head, B.J., Maas, M.L., Swanson, E.A., Moorhead, S., Reed, D., Conley, D.M., & Kozel, M. (2011). Most frequent nursing diagnoses, nursing interventions, and nursing-sensitive patient outcomes of hospitalized older adults with heart failure: part 1. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies & Classifications, 22(1), 13–22. doi:10.1111/j.1744-618X.2010.01164.x

Schulman-Green, D., Jaser, S., Martin, F., Alonzo, A., Grey, M., McCorkle, R., Redeker, N. S., Reynolds, N., & Whittemore, R. (2012). Processes of Self-Management in Chronic Illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 44(2), 136–144.

Seganfredo, D. H. & Almeida, M. A. (2011). Nursing outcomes content validation according to Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) for clinical, surgical and critical patients. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagen, 19(1), 34-41.

Vassilaki, M., Aakre, J. A., Cha, R. H., Kremers, W. K., St. Sauver, J. L., Mielke, M. M., Geda, Y. E., Machulda, M. M., Knopman, D. S., Petersen, R. C., & Roberts, R. O. (2015). Multimorbidity and Risk of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(9), 1783–1790. doi:10.1111/jgs.13612

Whelton, P. K., Carey, R. M., Aronow, W. S., Casey, D. E., Collins, K. J., Dennison Himmelfarb, C., DePalma, S. M., Gidding, S., Jamerson, K. A., Jones, D. W., MacLaughlin, E. J., Muntner, P., Ovbiagele, B., Smith, S. C., Spencer, C. C., Stafford, R. S., Taler, S. J., Thomas, R. J., Williams, K. A., & Williamson, J. D. (2018). 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 138(17), e426–e483. doi:doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

World Health Organization. (2015). Q&As on hypertension. Hypertension.

World Health Organization. (2016). Raised total cholesterol. Global Health Observatory data repository.

Author Bios

Hyunkyoung Oh, RN, MSN, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the College of Nursing at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM). Her research focuses on self-management for adults with chronic conditions using patient information and assistive technology. She leads a collaborative research team focused on aging (ACT) at the UWM. She has also studied nursing outcomes classification for supporting accurate evaluations of patient outcomes. Dr. Oh served as the principal investigator on this validation study.

Sue Moorhead, RN, PhD, FCNC, FNI, FAAN, is an Associate Professor in the College of Nursing at the University of Iowa and the director of the Center for Nursing Classification and Clinical Effectiveness. Her research focuses on the development and implementation of standardized nursing terminologies and effectiveness research. She is the lead editor of the Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC).