Abstract

The rapidly changing health care landscape and the need for up-to-date knowledge has required nurses to consistently be aware of current issues and trends. To stay abreast of developing information, nurses tend to use Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram. Most research on social media in nursing practice and nursing education has focused on strategies aimed at enhancing networks and branding among nurses. There does not appear to be any study that has described how nurses are interacting with specific forms of social media. A non-experimental multi-phase, descriptive study examined the most used social media platform, the amount of times it was used, and on what day and time it was used as a means of tailoring and delivering future messages using specific social media platforms. Findings suggest that nurses enrolled in academic programming present with unique demographic characteristics, as well as characteristics relating to their personal and professional responsibilities, that significantly impact on not only what they interact with online, but how often, when, and their degree of involvement. Marketing and promotional strategies aimed at nurses in academic programs should be tailored to reflect these specific characteristics. Future studies examining engagement with online materials among nurses working in the clinical setting is required to determine if similar traits related to social media engagement exist.

Introduction

The rapidly changing health care landscape and the need for up-to-date knowledge has required nurses to consistently be aware of current issues and trends. To stay abreast of developing information, nurses tend to use Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram. These platforms provide not only an avenue for knowledge uptake, but also a medium for organizational marketing and promotion that includes advertisements for nursing positions and career advancement; upcoming seminars, workshops, and courses; opportunities for involvement in nursing research; and engagement in various health care organizational committees and events.

An estimated 83% of all nurses engage in the use of at least one form of social media technology (Wang et al., 2019). This finding has led to the development of specific organizational marketing and promotional strategies that are aimed at nurses using social media across both universities and health care institutions to enhance recruitment and retention and to share information (Bali & Bélanger, 2019). Thus, it is important for both health care and academic institutions to focus on ways in which marketing and promotional strategies are being conducted, as well as how nurses are interacting with specific brands to capture, maintain, and promote active engagement with these strategies. The longer and more actively engaged nurses are with their attention to a particular brand, profile, or information, the more successful the marketing strategy is deemed to be and more likely the information will be used to guide best practices within clinical settings (Bali & Bélanger, 2019).

Most research studies on social media in nursing practice and nursing education have focused on strategies aimed at enhancing networks and branding among nurses (Shinners & Graebe, 2020). However, there does not appear to be any study that has described how nurses are interacting with specific forms of social media. In particular, studies examining the most favorable timing, format, and dose of information to nurses online to attract their attention has not been examined. Studies examining these details can provide insights into how to effectively deliver information online to nurses (Piscotty et al., 2016). Nurses tend to have sporadic involvement with different forms of social media and may use various platforms during times that may not be consistent with the general population. The purpose of this study was to examine the most commonly used social media platforms, the amount of times they are used, and on what day and time as a means of tailoring and delivering future messages using specific social media platforms. The program in question encompassed a culturally diverse student body of nurses. Posts that contained specific curricular content, professional development materials, and faculty opportunities were designed to reflect the learning needs of this group; the posts were then circulated on social media using varying mediums, dosages, and time intervals over a number of weeks.

Methods

This non-experimental multi-phase study examined the most commonly used social media platforms, the amount of times used, and on what day and time as a means of tailoring and delivering future messages using specific social media platforms. Prior to the start of the study, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn graduate programming accounts were created, followed by a series of social media content that focused on advertising the programs’ curricular content, professional development sessions, and faculty opportunities. This set of content became the social media campaign. These advertisements were in the form of posters and flyers. In total, 47 pieces of content were developed. Each content piece was classified as either an event, endorsement, or broadcast. A posting was classified as an event if it referred to a graduate information night, a professional development session, a community session, or a graduate session. Endorsements included a faculty biography and/or an alumni profile, while broadcasts consisted of general messaging from the program and/or an overview of the various means of connecting with the program through social media. Once each content piece was classified, it was then clustered into one of seven groups; each group served as a sub-campaign for testing during pre-determined time intervals. Each grouping contained at least one event, one endorsement, and one broadcast content piece.

The university branding guidelines were closely followed during the creation of the campaign materials. In addition, a number of workshops that addressed branding, design, and implementation of social media advertisements were attended in preparation for this study. Research ethics board approval for this study was not acquired, as personal data were not solicited from individuals who viewed or interacted with the campaigns that were posted. All data acquired were obtained directly through publicly accessible channels that included Hootsuite and Google Analytics (web traffic).

The study was conducted over a period of 18 weeks, in two phases. The initial phase of the study occurred over the first seven weeks. The results identified potential practical challenges that may arise during the conduct of the second phase of the study. In addition, findings were used to create a mechanism for ensuring consistency in delivery of content. During the first phase of the study, various content pieces were uploaded to social platforms. A schedule for posting of content was determined, as well as tools for collecting data. No practical challenges were identified. Following the first phase, all content posts were updated to reflect upcoming professional development opportunities, revised curricular issues, and new faculty opportunities. The revised campaign posts and the newly developed data collection tools were integrated into the second phase of the study, which lasted for 11 weeks to determine the optimal medium, dosage, and timing for delivering social media content.

Data were collected on the type of social media platform (e.g. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn) and the degree of engagement with each campaign (e.g. number of impressions, engagements, individuals reached, clicks, and total likes). Descriptive data analysis in the form of frequency counts was used to present data collected.

Results

Results from the preliminary phase of the study

During the preliminary phase of the study, the greatest number of individuals who viewed a particular posting on Twitter occurred between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. (10,037 impressions), with the least number of impressions occurring between 6 p.m. and 8 p.m. (337 impressions). The most frequent engagement on Twitter occurred between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. (223 likes, comments, or clicks), with the least active engagement period occurring between 6 p.m. and 8 p.m. (5); Table 1 provides more information on these results.

On Facebook, the most number of individuals were reached between 6 a.m. and 7 a.m. (2529 impressions), with the least effective time for reaching individuals being between 4:30 p.m. and 6 p.m. (461 impressions). The time interval that resulted in the greatest number of links clicked was between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. (38 clicks), while the time interval that generated the least number of links clicked occurred between 6 a.m. and 7 a.m. (2 clicks) (Table 2).

On Instagram, the time interval that generated the highest number of impressions was between 6 a.m. and 7 a.m. (198), while the time interval that generated the least number of impressions was between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. (36). The time interval that appeared to be most effective in reaching accounts was between 2 p.m. and 3 p.m. (207), while the least effective time interval for reaching accounts was between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. (27) (Table 3).

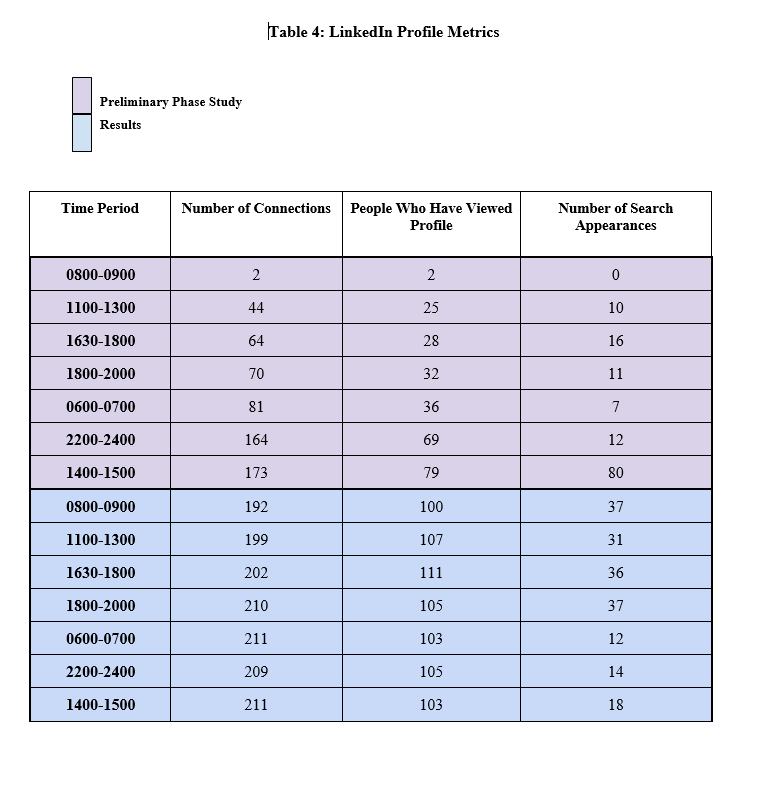

Finally, with LinkedIn, the most common time in which posts were viewed was between 2 p.m. and 3 p.m. (79), while 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. was the time interval when content was viewed the least (2) (Table 4).

Results from the final phase of the study

The largest volume of individuals who viewed a particular posting on Twitter occurred between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. (3114 impressions), with the least number of impressions occurring between 2 p.m. and 3 p.m. (325). The most frequent engagement on Twitter occurred between 11 p.m. and 1 p.m. (128), with the least active engagement period occurring between 2 p.m. and 3 p.m. (25) (Table 1).

With Facebook, the greatest number of individuals were reached between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. (2823 impressions), while the time interval that resulted in the most number of links clicked was between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. (48). (Table 2).

With Instagram, the time interval that generated the highest number of impressions was between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. (615), while the time interval for reaching the greatest number of accounts was between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. (401) (Table 3).

Finally, in terms of LinkedIn, the most common time in which posts were viewed was between 4:30 p.m. and 6 p.m. (111) (Table 4).

Discussion and Implication

Overview of social media platforms

Within this academic setting, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram were used as media for the delivery of materials within and outside of the institution. This is consistent to similar forms of social media used across academia globally (Masias et al., 2019). The use of social media content was found to be most effective in instances where the content was targeted for the delivery to specific audiences (Carmack & Heiss, 2018; Fardouly et al., 2017; Masias, et al., 2019). However, this strategy was only sporadically used throughout the graduate program. The study findings noted Twitter was being used intermittently to disseminate information; this implementation resulted in minimal uptake of content and engagement in various activities. Similarly, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram were also used infrequently to engage in conversations with individuals and/or organizations; to showcase products, workshops, and sessions; and to many individuals across a number of organizations.

Dosage refers to the number of times in which materials are provided to an individual and/or organization with the means of achieving desired outcomes (Bewick et al., 2017). Fluctuations in dosage may influence the effectiveness of social media campaigns in producing intended outcomes. Knowing optimal dosage can help tailor the delivery of specific social media content. To determine the most effective dosage, data was collected on both post and profile metrics. Within our study, dosage on Twitter was measured by 1) impressions, which is the number of individuals who viewed a particular posting, as well as by 2) engagements, which is the number of times individuals clicked, liked, or expanded on comments. With Facebook, dosage was measured through the number of individuals reached, number of clicks, and total likes. For Instagram, dosage was determined through the number of impressions and the number of accounts reached. Finally, regarding LinkedIn, dosage was presented through the number of connections that were made.

Timing was the final characteristic of interest related to social media campaigns and refers to the most effective time for delivering the social media campaign to illicit a response in the form of a view. Several time intervals of one, one-and-half, and two-hour blocks were identified for this study in which social media campaigns were delivered. These time intervals included: 6 a.m. to 7 a.m., 8 a.m. to 9 a.m., 11 a.m. to 1 p.m., 2 p.m. to 3 p.m., 4:30 p.m. to 6 p.m., 6 p.m. to 8 p.m., and 10 p.m. to midnight. These timings were chosen according to the study participants’ work and life schedules. Study participants consisted primarily of young to mid-adult (24-39 years of age) females, many of whom worked or had worked as registered nurses and were caring for families with one to two children under the age of five. Thus, the identified time periods were deemed as relevant to the study participants’ daily routines. For instance, 6 a.m. to 7 a.m. would be a relevant time interval as some of the study participants may be waking up and completing morning routines, while another set of participants may be finishing their night shift.

The study’s results showed the most frequent time interval for study participants to engage with Twitter was during lunch period, with afternoon and early evening hours being the least popular time for engagement with this social media platform. Typically, graduate students do not have classes during lunch hours. Students engaged in full-time studies usually have classes during the morning and afternoon hours, with an hour break in between. Twitter is a convenient tool that encompasses short commentaries and can be used during brief time intervals while allowing for quick updates on current events.

Tweeting or engaging on Twitter with graduate students during the lunch interval increases the likelihood of retweets and capturing an individual’s attention, participation in anticipated events, and uptake of key curricular messages. In addition, the use of applications that can spread tweets throughout the day, at key time intervals, can assist with the strategic delivery of promotional and/or curricular materials as a means of enhancing engagement among nurses.

The early morning hours (prior to class) appear to be the most convenient time for individuals to engage on Facebook. Facebook allows for community building – the sharing of thoughts, ideas, and photos; planning events; and the promotion and marketing of upcoming events, workshops, or sessions. During the early morning hours, nurses tend to be getting ready for the start of class and may have time available to engage on Facebook. During the evening hours, these nurses may either be coming home from school, getting ready for dinner, or preparing for an evening or night shift at work. Thus, their schedules may not allow for enough time to interact on Facebook, which in contrast to the short bursts of information found on Twitter, affords more lengthy opportunities to engage in discussions.

The Instagram findings suggest the highest number of impressions occurred during the early morning hours. An increased number of impressions is consistent with findings obtained from Fardouly et al. (2017), who also noted that Instagram was most popular with women between the ages of 25 and 35. This confirms our findings indicating that females comprised a key demographic of our study. Within this study, endorsement postings that consisted of colorful posters, flyers, and brochures that contained imagery and photos were among the most viewed items. For future promotion and marketing campaigns for this particular population, colorful materials with images and/or photos should be used to attract viewers and encourage engagement with graduate programming events.

On LinkedIn, a small number of individuals engaged in viewing and searching profiles. This may be due to the majority of individuals accessing required program and curricular information through other means, such as the University’s website, other social media platforms, or attending information sessions. In addition, studies have found that graduate students are infrequent and passive users of Linkedin as this medium does not easily allow for chats and conversations (Carmack & Heiss, 2018). Thus, parallel to our study, once students made connections with the program on Linkedin, they were no longer engaged in actively searching for curricular information, as reflected in the decrease in the number of search appearances.

Timing pertaining to the month in which social media content is dispersed can impact effectiveness. Even though similar results were obtained across both phases of the study, the number of individuals who were engaged in the preliminary phase of the study (which occurred over the summer months) was significantly lower than those who engaged in the main phase of the study (September to November). As a result, institutions should plan postings in accordance with the time of year.

It was also noted across all the social media platforms, between 10% to 30% of the various followers and/or connections were from spam accounts (i.e. robots, blank profiles). For future implementation of social media platforms, specific programs can be used to block the infiltration of spam/robots or to filter results and metrics.

Finally, studies have consistently identified nurses as one of the main group of professionals who infrequently use social media – with one of the main reasons being related to ethical and legal obligations in the workplace (Tuckett & Turner, 2016). However, when nurses do engage on social media, they tend to be drawn to Facebook for social rather than educational purposes (Tuckett & Turner, 2016). Instagram, Twitter, and Linkedin are also used but much more infrequently. As a result, the findings from this study may not being generalizable to other populations or programs.

The study findings are consistent with previous research in this area (Donelan, 2016), in that social media platforms are used as a tool for sharing of information throughout academia. However, no specific focus or attention is given to strategically using each social media platform to initiate or maintain a targeted marketing and/or dissemination campaign throughout university settings. Best practices focusing on the use of social media platforms throughout academia need to be developed so that strategic use of individual platforms can be initiated. For example, using Twitter for quick updates of current events, at specific points in time during the day; while using Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn for community building, visual sharing of messages, and career planning and recruitment, respectively. Best practices require a thorough understanding of the differences between various social media platforms and intentionally using each platform to maximize their potential reach. The results of this study provide a starting point for the development of a targeted social media campaign to reach current and future graduate nursing students, as well as alumni.

Conclusion

Within academia, the majority of research on social media has centered on strategies aimed at enhancing networks and branding, but there does not appear to be any specific study that has described how nurses are interacting with specific forms of social media. A multi-phase study was conducted to determine the most appropriate medium, dosage, and timing for delivering social media campaigns to enhance graduate nurses’ engagement with their curricula. Based on the study findings, the use of Twitter was identified as the most effective medium for quickly disseminating small bursts of information to nurses during the luncheon period. Facebook was found to be most effective when materials were sent during the early morning hours, just prior to the start of class. Nurses appeared to be highly engaged and interactive with Facebook during the 8 a.m. to 9 a.m. period. Instagram was identified as being most effective at various times throughout the day only when bright colorful images and photos were used. LinkedIn was identified as the least interactive social media platform. Timing related to month of delivery, the use of spam filters, and integration of techniques to spread out tweets to allow for retweets during the day were suggested as possible means of enhancing the effectiveness of various social media platforms. Findings suggest that nurses enrolled in academic programming present with unique demographic characteristics, as well as characteristics relating to their personal and professional responsibilities, that significantly impact on not only what they interact with online, but how often, when, and their degree of involvement. Thus, marketing and promotional strategies aimed at nurses in academic programs should be tailored to reflect these specific characteristics. Future studies examining engagement with online materials among nurses working in the clinical setting are required to determine if similar traits related to social media engagement exist.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog or by commenters are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HIMSS or its affiliates.

Online Journal of Nursing Informatics

Powered by the HIMSS Foundation and the HIMSS Nursing Informatics Community, the Online Journal of Nursing Informatics is a free, international, peer reviewed publication that is published three times a year and supports all functional areas of nursing informatics.

Bali, S., & Bélanger, C. H. (2019). Exploring the use of Facebook as a marketing and branding tool by hospital foundations. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 24(3), e1641. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1641

Bewick, B. M., Ondersma, S. J., Høybye, M. T., Blakstad, O., Blankers, M., Brendryen, H., Helland, P., Johansen, A., Wallace, P. Sinadinovic, K., Sundström, C. & Berman, A. (2017). Key intervention characteristics in e-health: Steps towards standardized communication. Int.J. Behav. Med. 24, 659–664 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9630-3

Carmack, H. J., & Heiss, S. N. (2018). Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict College Students’ Intent to Use LinkedIn for Job Searches and Professional Networking. Communication Studies, 69(2), 145-160. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2018.1424003

Donelan, H. (2016). Social media for professional development and networking opportunities in academia. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 40(5), 706-729. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2015.1014321

Fardouly, J., Willburger, B. K., & Vartanian, L. R. (2017). Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media & Society, 20(4), 1380-1395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817694499

Hay, B., Carr, P. J., Dawe, L. & Clark-Burg, K. (2017). “iM Ready to Learn”. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 35(1), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000284.

Masias, V. H., Hecking, T., Crespo, F., & Hoppe, H. U. (2019). Detecting social media users based on pedestrian networks and neighborhood attributes: an observational study. Applied Network Science, 4(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41109-019-0231-3.

Marwick, A., & Lewis, R. (2017). Media manipulation and disinformation online. New York: Data & Society Research Institute. https://datasociety.net/library/media-manipulation-and-disinfo-online/

Piscotty, R., Martindell, E., & Karim, M. (2016). Nurses' self-reported use of social media and mobile devices in the work setting. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics, 20(1).

Riff, D., Lacy, S., Fico, F., & Watson, B. (2019). Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research. Routledge.

Shinners, J., & Graebe, J. (2020). Continuing Education as a Core Component of Nursing Professional Development. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 51(1), 6-8. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20191217-02

Tuckett, A., & Turner, C. (2016). Do you use social media? A study into new nursing and midwifery graduates' uptake of social media. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 22(2), 197-204. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12411

Wang, Z., Wang, S., Zhang, Y., & Jiang, X. (2019). Social media usage and online professionalism among registered nurses: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 98, 19-26. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.06.001

Author Bios

Dr. Suzanne Fredericks is a nurse scientist whose program of research focuses on designing and evaluating interventions to support patients undergoing invasive surgical procedures. She has received advanced research methods training through the Canadian Institute of Health Research Randomized Controlled Trials Mentorship Training Program and the Cochrane Collaboration. Dr. Fredericks is an active researcher within the Cochrane Heart Group. Dr. Fredericks is a professor in the School of Nursing at Ryerson University. She is an active member of the Maurice Yeates School of Graduate Studies and functions as a graduate student thesis supervisor. Within the Master of Nursing Program, Dr. Fredericks teaches quantitative research methods courses.

Mr. Jacky Au Duong is the manager for marketing and promotion for the faculty of communication and design at Ryerson University. His expertise is in website management and design; documentation and archiving; training, recruitment, and staff support; and branding.

Ms. Paula Lamaj is completing her second year of the Undergraduate Collaborative Nursing Program at Ryerson University. She has served as a research assistant and has been instrumental in designing and evaluating social media-based interventions.