Cybersecurity in healthcare involves the protecting of electronic information and assets from unauthorized access, use and disclosure. There are three goals of cybersecurity: protecting the confidentiality, integrity and availability of information, also known as the “CIA triad.”

In This Guide

What is Cybersecurity in Healthcare?

Understanding Threats

Cybersecurity in Healthcare Best Practices

Cybersecurity in Healthcare Laws and Regulations

What is Cybersecurity in Healthcare?

Cybersecurity in Healthcare

In today’s electronic world, cybersecurity in healthcare and protecting information is vital for the normal functioning of organizations. Many healthcare organizations have various types of specialized hospital information systems such as EHR systems, e-prescribing systems, practice management support systems, clinical decision support systems, radiology information systems and computerized physician order entry systems. Additionally, thousands of devices that comprise the Internet of Things must be protected as well. These include smart elevators, smart heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, infusion pumps, remote patient monitoring devices and others. These are examples of some assets which healthcare organizations typically have, in addition to those mentioned below.

Email is a primary means for communication within healthcare organizations. Information of all kinds is transacted, created, received, sent and maintained within email systems. Mailbox storage capacities tend to grow with individuals storing all kinds of valuable information such as intellectual property, financial information, patient information and others. As a result, email security is a very important part of cybersecurity in healthcare.

Phishing is a top threat. Most significant security incidents are caused by phishing. Unwitting users may unknowingly click on a malicious link or open a malicious attachment within a phishing email and infect their computer systems with malware. In certain instances, that malware may spread via the computer network to other computers. The phishing email may also elicit sensitive or proprietary information from the recipient. Phishing emails are highly effective as they typically fool the recipient into taking a desired action such as disclosing sensitive or proprietary information, clicking on a malicious link, or opening a malicious attachment. Accordingly, regular security awareness training is key to thwart phishing attempts.

Physical Security

Unauthorized physical access to a computer or device may lead to its compromise. For example, there are physical techniques that may be used to hack a device. Physical exploitation of a device may defeat technical controls that are otherwise in place. Physically securing a device, then, is important to safeguard its operation, proper configuration and data.

One example is leaving a laptop unattended while traveling or while working in another location. Careless actions may lead to the theft or loss of the laptop. Another example is an evil maid attack in which a device is altered in an undetectable way such that the device may be later accessed by the cybercriminal, such as the installation of a keylogger to record sensitive information, such as credentials.

Legacy Systems

Legacy systems are those systems that are no longer supported by the manufacturer. Legacy systems may include applications, operating systems, or otherwise. One challenge for cybersecurity in healthcare is that many organizations have a significant legacy system footprint. The disadvantage of legacy systems is that they are typically not supported anymore by the manufacturer and, as such, there is generally a lack of security patches and other updates available.

Legacy systems may exist within organizations because they are too expensive to upgrade or because an upgrade may not be available. Operating system manufacturers may sunset systems and healthcare organizations may not have enough of a cybersecurity budget to be able to upgrade systems to presently supported versions. Medical devices typically have legacy operating systems. Legacy operating systems may also exist to help support legacy applications for which there is no replacement.

Healthcare Stakeholders

Patients

Patients need to understand how to securely communicate with their healthcare providers. Additionally, if patients engage virtually with their healthcare providers, whether through a telehealth platform, evisits, secure messaging, or otherwise, patients need to understand the privacy and security policies and also how to keep their information private and secure.

Workforce Members

Workforce members need to understand the privacy and security policies of the healthcare organization. Regular security awareness training is essential to cybersecurity in healthcare so that workforce members are aware of threats and what to do in case of actual security incidents. Workforce members also need to know who to contact in the event of a question or problem. In essence, workforce members can be the eyes and ears for the cybersecurity team. This will help the cybersecurity team understand what is working and what is not working in an effort to secure the information technology infrastructure and information.

C-Suite

More healthcare organizations now have a chief information security officer (CISO) in place to make executive decisions about the cybersecurity program. CISOs typically work on strategy, whereas individuals on the cybersecurity team that report to the CISO execute the strategy as dictated by the CISO. The CISO is an executive that ideally is on the same level as other C-suite executives, such as the chief financial officer, chief information officer, and so on. The greater the executive-level buy-in, the greater degree of top-down buy-in of the organization’s cybersecurity program.

Vendors/Market Suppliers

A major retailer was breached as a result of a major cyberattack on its heating, cooling, and air conditioning (“HVAC”) vendor system. Stolen credentials from the HVAC vendor were used to break into the retailer’s systems. In essence, this was a supply chain attack since the cyberattackers had compromised the HVAC vendor to ultimately target the retailer. Following this attack, cyber supply chain attacks compromised healthcare information systems through vendors’ stolen credentials.

Some large organizations have fairly robust cybersecurity in healthcare programs. However, many of these organizations also rely upon tens of thousands of vendors. To the extent that these vendors have lax security policies, or have inferior security policies, this can create a problem for the healthcare organization. In other words, stolen vendor credentials or compromised vendor accounts may potentially result in a compromise of the healthcare organization, such as through phishing or other means. A vendor may have elevated privileges to a healthcare organization’s information technology environment and, thus, a compromise of a vendor’s account or compromised credentials may lead to elevated access by an unauthorized third party (a cyberattacker) of a healthcare organization’s information technology resources.

Understanding Threats

Ransomware and Other Malware

Ransomware is a significant threat to the confidentiality, integrity and availability of information. When a machine or a device is infected by ransomware, the files and other data are typically encrypted, access is denied and ransom is demanded. In essence, the data is held hostage by the cybercriminal and a demand is made to pay the ransom in order for the data to be returned back to the user. However, paying the ransom is not a guarantee that the data will be restored. In some cases, the ransom may be paid, but the data may never be restored despite promises to the contrary.

In addition to ransomware, there are many other types of malware that pose a threat to healthcare organizations. These include credential stealers whereby usernames, passwords and other tokens are stolen by cybercriminals and wipers in which entire disk drives may be erased and the data may be unrecoverable.

Phishing

Threats to computer systems and devices are not just simply malware, however. Phishing is typically the initial point of compromise for significant security incidents. Phishing is particularly effective since the individual user is targeted and may be fooled into disclosing sensitive information, clicking on a malicious link, or opening a malicious attachment.

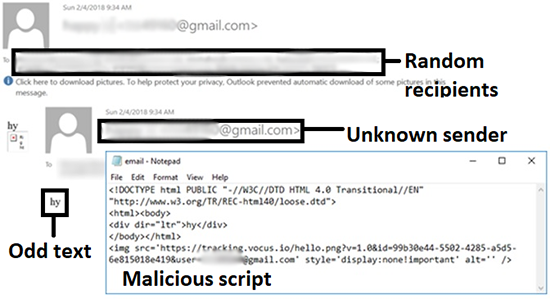

Phishing emails tend to be the most common form of phishing, although phishing may also occur by way of websites, social media, text messages, voice calls, and the like. Hallmarks of phishing emails may include poor spelling and grammar (although not always), too good to be true claims, and language that conveys a sense of urgency or which preys on an individual’s fear or greed. General phishing emails are those emails that are not sent to specific recipients and that do not contain tailored content. Essentially, general phishing emails are a one size fits all.

Example of general phishing email, source: HIMSS Cybersecurity Community

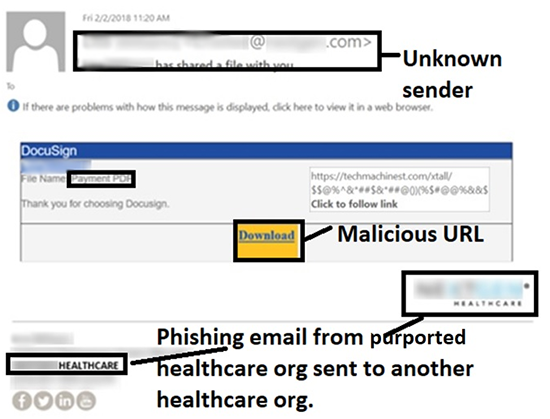

Alternatively, an online scam artist may send a spear-phishing email to a specific employee within an organization or to a specific department or unit within an organization. Unlike general phishing emails, spear-phishing emails are tailored to the targeted recipients. Because spear-phishing emails are targeted, they tend to be more effective than general phishing emails. In other words, spear-phishing emails tend to have a higher click rate/response rate than general phishing emails.

Example of spear-phishing email, source: HIMSS Cybersecurity Community

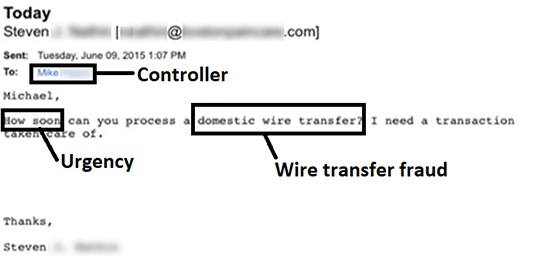

Like spear-phishing, whaling emails are also tailored to the recipient. Whaling occurs when an online scam artist targets a “big fish” (i.e., a c-suite executive, such as the CEO, CFO, CIO, etc.). As an example, a whaling email may be sent from an online scam artist to a chief financial officer in order to convince him or her to wire funds to an account that is controlled by the online scam artist. Like other kinds of phishing, the objective of whaling is to deceive the target, but not to arouse suspicion about the ruse.

Example of whaling email, source: HIMSS Cybersecurity Community

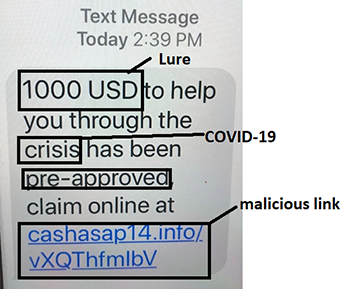

Other forms of phishing exist, such as, but not limited to, SMS phishing (also called SMiShing). This is when the online scam artist crafts a deceptive message to the target via a text message to a mobile phone.

Example of SMiShing, source: HIMSS Cybersecurity Community

Reimagine Health: HIMSS Global Health Conference

March 14-18, 2022

Join changemakers at HIMSS22—in person and digitally—as we reimagine health together through education, innovation and collaboration.

Cybersecurity in Healthcare Best Practices

HIMSS TV deep dive into cybersecurity in healthcare.

Risk Assessments

Risk assessments are the cornerstone of every program for cybersecurity in healthcare. Risk needs to be assessed first before any action is taken to help manage the risk. Risk must be gauged based upon factors such as probability of occurrence, impact on the organization, as well as the prioritization of the risk. Risk assessments should be conducted or reviewed regularly and at least once per year.

Security Controls

Ideally, every healthcare organizations should have basic and advanced security controls in place. Doing so will help ensure that there is defense-in-depth such that if one control fails, another control will take its place. As an example, a virus may enter through an organization’s firewall, but it may be blocked by an anti-virus program. However, not all security incidents can be prevented. This is where blocking and tackling comes into play. A robust incident response plan is necessary for cybersecurity in healthcare so that any security incidents that occur are either blocked or tackled in a timely and expeditious manner.

Basic security controls include the following:

- Anti-virus

- Backup and restoration of files/data

- Data loss prevention

- Email gateway

- Encryption at rest

- Encryption for archived files/data

- Encryption in transit

- Firewall

- Incident response plan

- Intrusion detection and prevention system

- Mobile device management

- Policies and procedures

- Secure disposal

- Security awareness training

- Vulnerability management program/patch management program

- Web gateway

Advanced security controls include the following:

- Anti-theft devices

- Business continuity and disaster recovery plan

- Digital forensics

- Multi-factor authentication

- Network segmentation

- Penetration testing

- Threat intelligence sharing (also called information sharing)

- Vulnerability scans

Cybersecurity in Healthcare Laws and Regulations

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is a federal requirement in the U.S. which applies to covered entities and business associates. HIPAA consists of the HIPAA Privacy Rule, Security Rule and Breach Notification Rule. Covered entities include health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, and healthcare providers who electronically transmit any health information in connection with transactions for which the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has adopted standards.

Examples of covered entities include physician practices, ambulatory surgical centers, hospitals, long-term care facilities, health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, among others. Business associates perform functions or services on behalf of covered entities. Business associates may create, receive, transmit, or maintain protected health information on behalf of the covered entity. Examples of business associates include accountants, attorneys, cloud service providers, document storage companies, third party billing services and others.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule, 45 CFR Part 160 and Subparts A and E of Part 164 , sets forth permitted and required uses and disclosures of protected health information. The protected health information may exist in any form, including on paper, film and in electronic form. Protected health information is a form of individually identifiable health information.

The HIPAA Security Rule, 45 CFR Part 160 and Part 164, Subparts A and C, sets forth requirements for electronic protected health information. In other words, the confidentiality, integrity and availability of electronic protected health information must be maintained by covered entities and their business associates.

The HIPAA Breach Notification Rule, 45 CFR §§ 164.400-414, requires HIPAA covered entities and their business associates to provide notification following a breach of unsecured protected health information.

A breach is, generally, an impermissible use or disclosure under the Privacy Rule that compromises the security or privacy of the protected health information. An impermissible use or disclosure of protected health information is presumed to be a breach unless the covered entity or business associate, as applicable, demonstrates that there is a low probability that the protected health information has been compromised based on a risk assessment of at least the following factors:

- The extent to which the risk to the protected health information has been mitigated

- The nature and extent of the protected health information involved, including the types of identifiers and the likelihood of re-identification

- The unauthorized person who used the protected health information or to whom the disclosure was made

- Whether the protected health information was actually acquired or viewed

Covered entities and business associates, where applicable, have discretion to provide the required breach notifications following an impermissible use or disclosure without performing a risk assessment to determine the probability that the protected health information has been compromised.

There are three exceptions to the definition of breach:

- The covered entity or business associate has a good faith belief that the unauthorized person to whom the impermissible disclosure was made, would not have been able to retain the information.

- The inadvertent disclosure of protected health information by a person authorized to access protected health information at a covered entity or business associate to another person authorized to access protected health information at the covered entity or business associate, or organized healthcare arrangement in which the covered entity participates. In both cases, the information cannot be further used or disclosed in a manner not permitted by the Privacy Rule.

- The unintentional acquisition, access, or use of protected health information by a workforce member or person acting under the authority of a covered entity or business associate, if such acquisition, access, or use was made in good faith and within the scope of authority.

Similar to a covered entity, a business associate also is directly liable and subject to civil penalties for failing to safeguard electronic protected health information in accordance with the HIPAA Security Rule. Additionally, covered entities must establish business associate agreements with their business associates.

A business associate agreement is a written contract between a covered entity and a business associate which must address the following:

- Authorize termination of the contract by the covered entity if the business associate violates a material term of the contract

- Establish the permitted and required uses and disclosures of protected health information by the business associate

- Provide that the business associate will not use or further disclose the information other than as permitted or required by the contract or as required by law

- Require the business associate to implement appropriate safeguards to prevent unauthorized use or disclosure of the information, including implementing requirements of the HIPAA Security Rule with regard to electronic protected health information

- Require the business associate to report to the covered entity any use or disclosure of the information not provided for by its contract, including incidents that constitute breaches of unsecured protected health information

- Require the business associate to disclose protected health information as specified in its contract to satisfy a covered entity’s obligation with respect to individuals' requests for copies of their protected health information, as well as make available protected health information for amendments (and incorporate any amendments, if required) and accountings

- To the extent the business associate is to carry out a covered entity’s obligation under the Privacy Rule, rRequire the business associate to comply with the requirements applicable to the obligation to the extent the business associate is to carry out a covered entity’s obligation under the Privacy Rule

- Require the business associate to make available to HHS its internal practices, books and records relating to the use and disclosure of protected health information received from, or created or received by the business associate on behalf of, the covered entity for purposes of HHS determining the covered entity’s compliance with the HIPAA Privacy Rule

- Require, at termination of contract if feasible, the business associate to return or destroy all protected health information received from, or created or received by the business associate on behalf of, the covered entity

- Require the business associate to ensure that any subcontractors it may engage on its behalf that will have access to protected health information agree to the same restrictions and conditions that apply to the business associate with respect to such information

- Authorize termination of the contract by the covered entity if the business associate violates a material term of the contract.

HIPAA is enforced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights (OCR). OCR has the authority to interpret and enforce HIPAA. Accordingly, it is best for to keep up with guidance from OCR as it relates to the interpretation and enforcement of HIPAA.

42 CFR Part 2

42 CFR Part 2 protects patient records created by federally funded programs for the treatment of substance use disorder. At the state level, healthcare provider organizations must also be aware of other applicable privacy and security laws. Certain special types of health information are deemed to be super protected health information under state law. Examples include records related to drug and alcohol abuse, HIV-related information, and the like.

Section 5 of Federal Trade Commission Act

Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act applies to entities other than not-for-profit entities. Specifically, Section 5 of the FTC Act provides that “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce… are… declared unlawful.” The failure of an organization to adequately safeguard computer systems and infrastructure may be deemed to be “unfair” according to the FTC. Additionally, a deceptive practice is one in which consumers are falsely misled into believing that their privacy and/or security of their information is safeguarded.

European Union General Data Protection Regulation

Any organization that processes the personal data of data subjects (people) in the European Union must comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). “Processing” includes data collection, storage, transmission, analysis and the like. “Personal data” is any information that relates to a person, such as without limitation names, email addresses, IP addresses, eye color and the like—essentially, any personally identifiable information or information that may be identifying of an individual.

GDPR is broader than HIPAA and regulates any information that may be used, directly or indirectly, or identify a person that is in the European Union. In other words, GDPR applies to many types of personal information, whereas HIPAA regulates protected healthcare information. Even if an organization is located outside of the European Union, GDPR may still apply if:(1) the organization offers goods or services to individuals within the European Union (whether or not a payment is required from them) or (2) the behavior of individuals in the European Union is monitored by the organization. Additionally, GDPR applies to both controllers and processors. A “controller” means a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which, alone or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data. A “processor” means a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which processes personal data on behalf of the controller.

In order to lawfully process the information of a data subject, there must be a lawful basis for doing so. Lawful bases include the following:

- Consent from the data subject

- Performance of a contract, where the processing of the data is necessary

- Where the processing is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by a controller or processor

Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) applies to private-sector organizations across Canada that collect, use or disclose personal information in the course of a commercial activity. Hospitals are generally governed by provincial laws in Canada, but PIPEDA may apply in certain instances.

Certain types of information are excluded from PIPEDA. Business contact information such as an employee’s name, title, business address, telephone number or email addresses that is collected, used or disclosed solely for the purpose of communicating with that person in relation to their employment or profession.

Cybersecurity in healthcare threats continue to evolve and, in turn, so must cybersecurity solutions to combat these threats. In order to stay ahead of these threats, we must increase our situational awareness about what is happening and share more information about what is going on with our peers and colleagues. Healthcare organizations must continue to support cybersecurity professionals as they help to safeguard patient data. There is no better time than the present to increase cybersecurity defenses, while enhancing the capabilities and knowledge of staff.